Network Structure, Culture & the Division of Labor

Director of Fox International Fellowship and Professor of Sociology and the School of Management

Jun 11, 2024

Compendium

Director of Fox International Fellowship and Professor of Sociology and the School of Management

Jun 11, 2024

Compendium

Adam Smith was so captivated by the division of labor that he allegedly fell into a Glaswegian tanning pit while describing its properties to a friend, Charles Townshend. While describing how tasks were split up between laborers in the tannery, Smith reportedly walked straight off a plank suspended above a foul mixture of fat and lime. Luckily for us, he survived the fall to continue his exploration of the idea, and that of morality in human relationships. When he published his great work of political economy, An Inquiry into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations, the core idea, and the answer to the puzzle posed in its title, was the relationship between the division of labor, productivity, and wealth. For Smith, the idea of the division of labor was endlessly fascinating because it creates an unintended but remarkably beneficial side-effect of human interactions. Individuals and nations did not trade with each other to benefit society or their fellow human being, but to benefit themselves. And yet, the division of labor helps everyone.

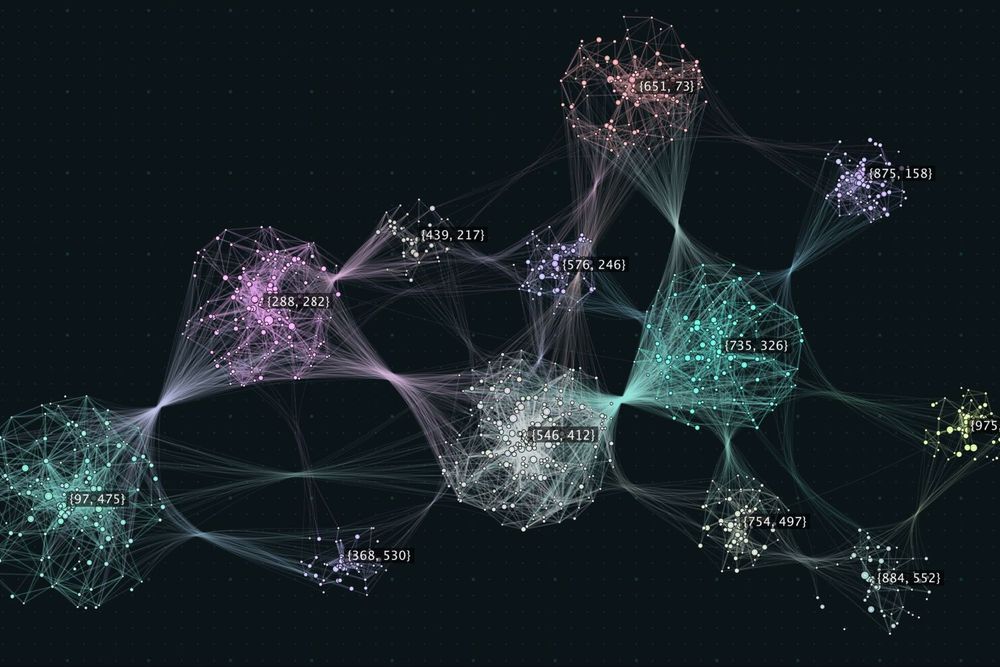

The division of labor remains a primary engine of economic growth and central to firm productivity. So it is important to ask, do we have to rely entirely upon an invisible hand to bring it about? My research on organizational and social networks explores this question. Using computational models and historical records, I have sought to understand the benefits of balancing centralized and decentralized control, and I have explored this tradeoff in a variety of contexts, some from different centuries. My first book, Between Monopoly and Free Trade, considered the balance between centralized control of the firm and the strong decentralized control exerted by the captains of the East Indiamen vessels that carried Europe’s trade to the East. I found that the strong autonomy of the ships’ captains aided the firm — both by increasing its flexibility while also promoting a robust channel of communication between captains. The partial surrender of centralized control made the firm a powerhouse over the long term.

This content is available to both premium Members and those who register for a free Observer account.

If you are a Member or an Observer of Starling Insights, please sign in below to access this article.

Members enjoy full access to all articles and related content from past editions of the Compendium as well as Starling's special reports. Observers can access a limited number of articles and may purchase articles on an ala carte basis.

You can click the 'Join' button below to become a Member or to register for free as an Observer.

Join The Discussion